Grand slices of life

Romance. Joy. Excess. Frivolity. Fun! Finally free from the pandemic, everyone who can is determined to make up for all that lost time, from drinks with friends to a trip round the world. It doesn’t matter what as long as it is joyous and celebrates life. Two new exhibitions at glorious Waddesdon Manor, Buckinghamshire, capture that prodigious mood in this magnificent setting, itself designed to propagate joy and delight: Wedding Cake (opens June 18) by Joana Vasconcelos and Do You Remember Me? by figurative painter Catherine Goodman.

Satyr among the sybarites

We all have our own sense of the Bloomsbury Group. Visually distinctive and alluring, optimistic, fundamentally grand even while living in a farmhouse. Memorable too for the short-lived Omega Workshop, and for Dorothy Parker’s smart tag of living in squares and loving in triangles. The group’s sexual freedom did not escape notice. Television currently loves anything to do with these pretty bright bed-hoppers. And now there’s more: the reappraisal by the Philip Mould Gallery in London of an overlooked member: sculptor Stephen “Tommy” Tomlin. This fresh appraisal follows the 2020 publication of Bloomsbury Stud, a biography by Michael Bloch and Susan Fox, from which the exhibition is named.

Turner Continental

In a prodigious and artistically ground-breaking life, Joseph Mallord William Turner (born 1775, died 1851) completed tens of thousands of sketches. These were mainly done very fast in pencil in sketch-books but also on loose leaves and at least once into a travel book he had rebound with interspersed blank pages for drawing. He then used them as source material in his studio, furnishing his deep affinity with Europe, explored in the London National Gallery’s new two-painting show, Turner on Tour.

Cezanne’s palette

As soon as possible, leave London and take a trip to Aix-en-Provence, France — not by braving rail strikes and Coronavirused flights but by getting to Tate Modern as fast as your legs or other means can carry you, in order to be transported to turn-of-the 20th century France courtesy of Paul Cezanne (1839-1906). This new, once-in-a-lifetime major exhibition comes from America. At the Tate it’s not only a well displayed and selected delight, but literally whisks the viewer off to blue-skied bays; to leafy shaded avenues winding among rustling green trees; to distant hazy vistas…

Lucian Freud rebooted

Lucian Freud is so famous for the brilliant distinction of his portraits that looking at his works afresh, untrammelled by his renowned family and racy personal life, is probably impossible. But commendably, the National Gallery’s new show (to January 22, 2023) successfully offers a version of it in a sort of clean-lined Freud reboot. Essentially chronological, this marvellous show only includes paintings by Freud, rather than “contextualising” the work via a few others’ paintings — and only divides into five themed rooms.

Sink or swim

Ten years after it first opened, Hastings Contemporary marks the moment with a Seafaring, a fitting exhibition of about 50 works. The galleries and circulation spaces are wearing well and the good café is staffed with gusto, which all adds to the charm of an ancient fishing town with higgledy streets, a funicular (currently being renovated); an endlessly long beach of shingle, and too many seagulls for their own good. Throw in a small seafaring museum in an old chapel (free) and it’s definitely worth a jaunt.

Touch paper for Modernity

Walter Sickert is a painter who somehow falls between the gaps. Born in 1860 in Germany, his life and work spanned across two centuries. To be 40 as one enters a new century is always tricky as an artist. Does one’s art (and one) belong to the old or the new? Sickert’s parents brought him to England when he was eight. Here he fundamentally stayed, becoming a leading light of the Camden Town Group. He had several studios in Camden and began to paint working -class people in either claustrophobic conversation pieces; out having fun at the music hall (the men in dark suits, with worn faces, lit by the spectacle); and prostitution or sex. His paintings are often ambiguous, including his speciality of a naked woman on a crumpled bed, often iron, legs splayed towards the viewer/voyeur. Decades later, Lucien Freud turned this image to gold in his own oevre. Freud’s 1972 Naked Portrait hangs nearby to drive the point. Evidently, Sickert lit the touch-paper.

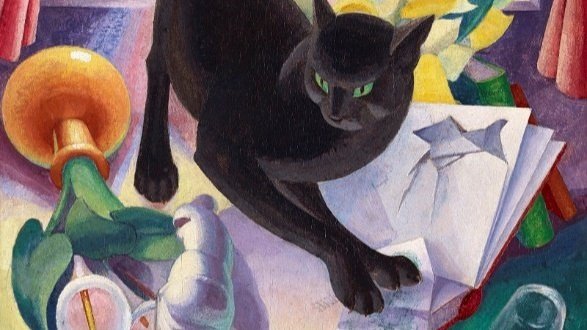

A cat’s paw of a conundrum

There’s a lot of debate over whether exhibitions of “women painters” are a good thing. The fundamental debate isn’t new. After the First World War, Scottish painter Norah Neilson Gray was furious that the Imperial War Museum wanted to buy her painting of a doctor inspecting injured soldiers in a makeshift Scottish hospital in an abbey cloister in France as part of its “Women’s Work” collection, rather than simply as an ungendered painting offering useful commentary on war. Quite right.

However, Charlotte Rostek, the author of the excellent accompanying book about Scottish Women Artists, a new exhibition of 50 artworks (the majority paintings) in the remarkable Sainsbury Centre outside the attractive market town of Norwich, maintains “it is still necessary to right a balance, for even if the present may seem triumphantly hopeful, the past is still yet to be wholly won.”

Ottimo Universale: Raphael

Five hundred years is a long time for anything to survive let alone a painting on a wooden panel prone to cracking, warping, or going up in flames — plus a skim of rabbit glue and chalk, or similar, topped with pigment and oil — yet, because of Raffaello Santi da Urbino’s undeniable brilliance of technique as well as representation, the National Gallery has been able to pull off the greatest Raphael (1483-1520) show ever. It pays tribute to director Gabriele Finaldi, who has set the NG alight with one cracker after another. For the first time, Raphael’s whole orbit of ability is represented in a dazzling UK show (April 9-31 July).

Utopian in Utopia

UTOPIAN IN UTOPIA

Langlands & Bell at Charleston, Sussex

By Philippa Stockley

Artists, especially painters, always seem rich in privilege, able to create worlds and dreams out of a few tubes of oil mixed with crushed pigment; and to provide escapism and inspire dreams in those who see them. So, now that its creators are long dead, the completely magical house of the Bloomsbury Group (as they came to be known) who created their own world at Charleston in Sussex is a perfect setting for other artists to be shown in and to explore, starting with a triple exhibition by British artist duo, Langlands & Bell.

In Search of Alice

By PHILIPPA STOCKLEY

If like so many of us you are fascinated by the lives of people born incredibly rich in past centuries, particularly the few independently wealthy women who kept control of their own money and lives, from Elizabeth I to Beatrix Potter, then Alice’s Wonderlands, the new exhibition at Waddesdon Manor in Buckinghamshire, is a must. The palatial mansion, built between 1874-1883 as a weekend retreat by Ferdinand de Rothschild (1839-1898), after the death of his father, Anselm von Rothschild, in the style of a 16th century French château (but with all mod cons including many bathrooms), houses a show exploring the life of Alice de Rothschild (1847-1922), for the first time.

A Prance to the Music of Time

By PHILIPPA STOCKLEY

‘The truly fashionable are beyond fashion.’ So wrote Cecil Beaton, the photographer who could conjure a princess out of anybody including our own, actual, princesses. Beaton’s home-made party coat of corduroy with whipped-up roses and wool-bobbled leaves, made with the same romantic brio he used to photograph his famous sitters, is in one of many good garment groupings in Fashioning Masculinities. But, as this large well-structured exhibition proves, the truly fashionable are also slap in the middle of fashion, making it as they go along; out of it for a millisecond until spotted and copied, then sucked into the mainstream by their startle and success. For the show brilliantly emphasises, with groupings on dais and wall — good paintings, good sculpture, good film — as well as in vitrines, the coincidences, collisions, reverberations and reflections that reach so easily from the 17th century to last year in a glad-handing joyfulness of cut, colour, fabric and feeling.

A World of Marvels

By PHILIPPA STOCKLEY

Why is it that children and teenagers who love doing meticulous drawings revere Albrecht Dürer, whom they seem to discover by osmosis? Or what about his strokable Young Hare of 1502, so warm and heavy in its furry contentment that its nose twitches; or his dazzling 1498 self-portrait as a stylish 26-year-old, with hyper-realistic curling long hair.

Those two images are so widely known that it’s no lack that they’re not in the National Gallery’s new blockbuster, Dürer’s Journeys, which has 135 engravings, woodcuts, paintings, drawings, plus some rare diary and journal pages. More than 80 works are by the prolific German genius, others by contemporary Netherlandish masters such as Quinten Massys, Lucas van Leyden, Bernaert van Orley and Jan Gossaert. Most have never been shown here. There are numerous detail-filled engravings, such as St Eustace (c.1500), including wonderful animals with warm weighty bodies and feeling faces — from lions, horses and dogs to snuffling pigs, and even a red-bottomed baboon.

Vive la Différence

By PHILIPPA STOCKLEY

Here’s William Hogarth, laugh-aloud funny; sly; satirical; sharply observant, and technically brilliant. In a slightly baggy, but also wonderfully massive exhibition, Tate Britain’s new show, Hogarth and Europe, has more than 60 Hogarths (paintings and prints) and a similar number by European contemporaries. Some highlights haven’t been seen here for decades, such as Hogarth’s superb portrait of independent Miss Mary Edwards (1742) who owned many of his works. In sultry crimson silk, diamonds and pearls, she is regally surrounded by clear signs of her wealth and power, including a portrait bust of Elizabeth I.