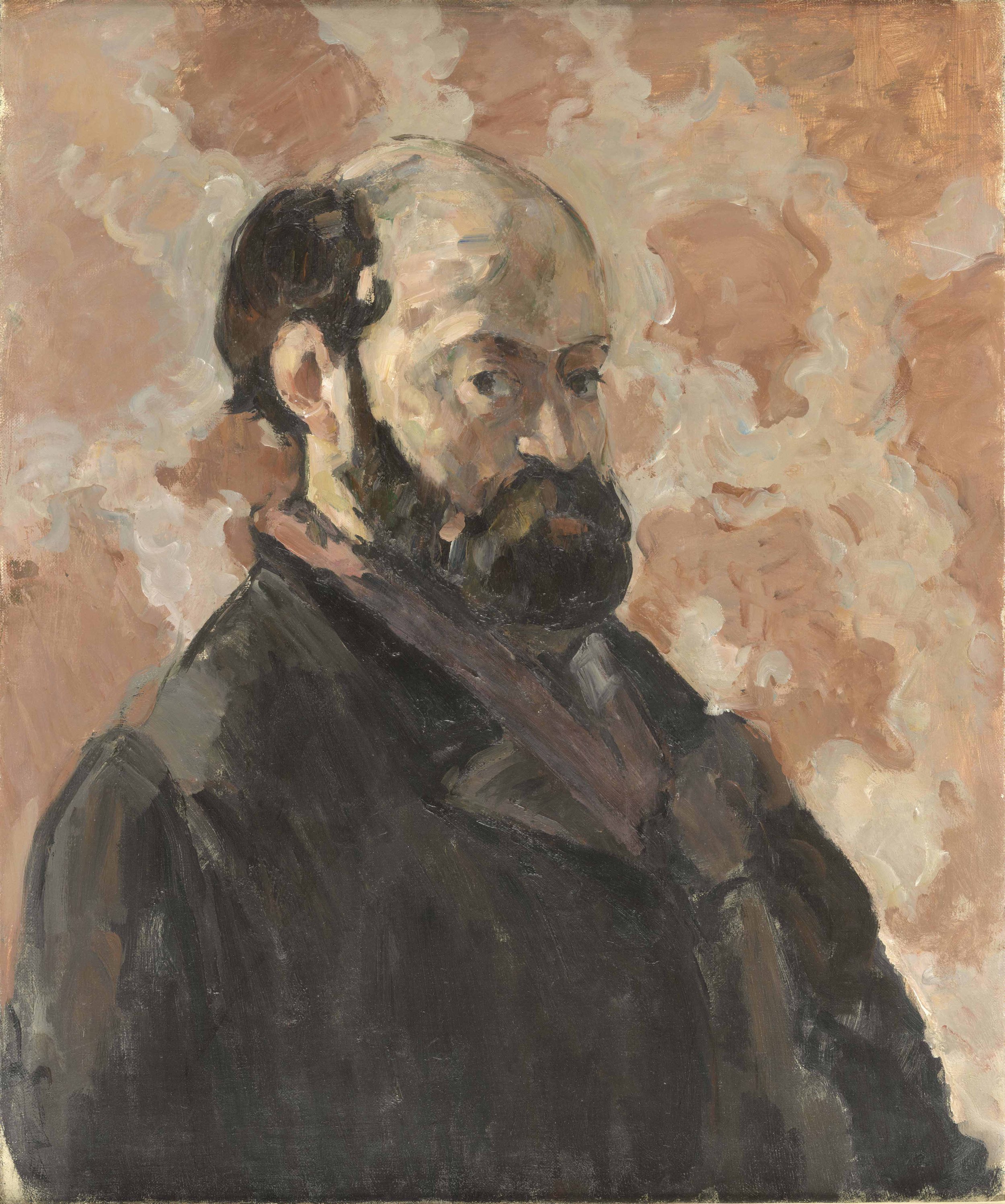

Cezanne’s palette

Paul Cezanne: Portrait of the Artist with Pink Background 1875. Paris, Musée d'Orsay, donation de M. Philippe Meyer, 2000. Photo (C) RMN-Grand Palais (musée d'Orsay) / Adrien Didierjean. It’s worth going just to see this.

As soon as possible, take a trip to Aix-en-Provence, France — not by braving rail strikes or Coronavirused flights but by getting to Tate Modern, London, as fast as your legs or other means can carry you, in order to be transported to turn-of-the 20th century France courtesy of Paul Cezanne (1839-1906). This once-in-a-lifetime major exhibition comes from the Art Institute of Chicago, which set it up with the Tate. At the Tate it’s important as there are 20 works never before shown in the UK (and likely not again in any reader’s lifetime). Beyond that, it’s not only a well displayed and selected delight, but literally whisks one off to blue-skied bays; to leafy shaded avenues winding among rustling green trees; to distant hazy vistas of Mont Saint-Victoire, the curvaceously hipped mountain that Cezanne loved and painted almost as frequently and lovingly as Claude Monet did haystacks. An entire, calm room is dedicated to it. Picasso even bought a bit of the mountain, in homage to his great painter-hero.

·Paul Cezanne: Mont Sainte-Victoire 1902-6. Philadelphia Museum of Art. Gift of Helen Tyson Madeira, 1977. Never previously shown in the UK.

Alongside these vistas in which, if you look closely, the painter used very little black, which goes a long way to create their tonal joie de vivre (the same with a lot of the still lives and the nudes. Not all, no, but a great many) are his familiar, beloved, sensuously solid pictures of apples and pears strewn among various cloths, plates, bowls and bottles; wonderful family portraits, and the spectacular large Bathers from the National Gallery, which is shown among other thematically similar paintings.

Paul Cezanne: Bathers c 1894-1905. Presented by the National Gallery, purchased with a special grant and aid of the Max Rayne Foundation, 1964

It's impossible not to come out of this show with a spring in one’s step and love in one’s heart for humankind, and to look at the glitter on the Thames with renewed appetite for life.

Paul Cezanne’s watercolour box (one of four on show) Photo © Stockley

Paul Cezanne’s last palette on show for first time. Photo © Stockley

Eighty or so works, mostly oil paintings, are offset by one or two unfinished pictures; some interesting sketchbooks from other artists who made sketches from Cezanne; an exciting vitrine holding the painter’s (rather gloomy looking) final palette, as well as four well-used watercolour boxes (these materials on show for the very first time, so very moving to see). There are also two gigantic blown-up photos. One is of the painter setting out to paint, looking satisfactorily every inch a painter. The other is the large, attractive house, Jas de Bouffon, part of the estate that he, his mother and his sisters inherited in 1886. It meant he could have a permanent studio and paint series of still lives as well as larger works.

Today it's hard to grasp why Cezanne was refused entry into the prestigious Paris Salon 14 times, from his 20s to his 40s. To our eyes these fresh, joyful and evocative works are bang on, about as perfect as paintings can be. But that was the problem — no one had seen anything like them before and the jury didn’t get it and like it. Fortunately, Cezanne, as a ‘Réfusé’ (itself quickly a badge of honour among the avant-garde), began to show in the Impressionist exhibitions as that movement found its identity and took off. In this way, although it took him a relatively long time, he became, firmly, part of the future rather than the past.

Paul Cezanne was born in Aix en Provence in 1839. His father wanted him to go into law. Thankfully he didn’t. His childhood friend, writer Emile Zola, encouraged him and later often reviewed his work — though Zola eventually wrote to the effect that Cezanne had lost his way. But many painters were so impressed by Cezanne’s paintings that they bought them. Among them his close friend Pissarro, who had the largest collection, but also Gauguin, Degas, Monet, and later on Picasso. And … Zola.

Paul Cezanne: Curtain, Pitcher and a Fruit Bowl, 1893. Photo © Stockley

The exhibition gives one the chance to get up close and see how generously loaded brushes of paint were used, often on fairly narrow straight or filbert hog brushes and often with shortish flat repeated — almost melodic; certainly methodical — strokes, building up colour with clear marks between colour variations. When in the mood, Cezanne could paint more smoothly and sometimes, as in the beautiful still life Curtain, Pitcher and a Fruit Bowl, 1893 (above) he evidently was. Here you can feel the softness or silkiness of fruit skin and sense the cool lustrous gleams of the grey ceramic vessel. In the compelling large early portrait Scipio, 1866-8, (below) he brushed long, fast, Impressionistic lines: curvy ones that so quickly create fabric folds at the trouser knee done with whitened blue; and skipping creamy yellow highlights to the arm, probably done with whitened yellow-ochre. The energy and dynamism of his method is very clear here.

Paul Cezanne: Scipio, 1866-8. Photo © Stockley

Cezanne’s inventive way of painting [white] flesh, using both rosy or ochre colours and blues almost apparently indiscriminately at times, must have seemed explosive and confusing. We see it normalised by painters such as Picasso, who followed. The way Cezanne moulded figures with scant regard to anatomy is also fascinating and again — to us — completely acceptable.

The rare chance to view his landscapes and coast-scapes in such large groups is rewarding and beautiful. He was one of very few painters who could make Viridian green — a strident, harsh, synthetic-looking green — seem natural, vibrant, verdant, fresh, sunlit and alive. His love of and harmony with the countryside is entirely clear from the animated, familiar, loving way he paints it. See it in The Avenue at the Jas de Bouffon, 1874-5 (below) — but also in many others.

Paul Cezanne: The Avenue at the Jas de Bouffon 1874-5. Photo © Stockley

House and estate, Jas de Bouffon, at Tate. Photo (of photo) © Stockley

One of the things that strikes is that practically everything Cezanne painted, apart from having mass and roundness, appears curved, sometimes almost human within the composition. Clouds practically have buttocks, hillsides have muscles; trees move with gently undulating arms. Even a wet leaded Paris rooftop — done during his fairly short year or two in Paris — has an organic, tactile allure — while still looking like itself and of itself. Go and judge for yourself.

Paul Cezanne: Rooftops in Paris. 1882. Photo © Stockley

THE EY EXHIBITION: CEZANNE

Tate Modern Southbank London

Until 12 March 2023

No images may be taken from this blog or used in any way whatsoever. All are under strict and exclusive copyright.

Cezanne, larger than life. Tate Modern. Photo (of photo) © Stockley